The Infamous Doctor Brinkley

It's an October Sunday morning, 1964. The fall foliage is in its prime. You decide to skip church and go for a ride in the country instead. You did Stagecoach Road to Benton to Mabelvale and return last Sunday, and The Highway 10 to Lake Maumelle to Bigelow then across the toadsuck ferry to Conway and return loop the week before. Highway 165 to Scott to England to Redfield and return is boring. Hey, Arch Street Pike, that's it. You haven't been out that way in a long while. Arch Street Pike to East End to Sheridan (excuse me, that's "Sherdin") to Redfield and return is a good ride. So off you go.

You go east on 65th, cross under the new bypass, and hit Arch Street just a quarter mile south of the rock crusher that has taken over both sides of the pike, and even has conveyors running across the roadway way up high. You don't go that way unless you want your car to get dirty, because everything for a half-mile radius is strewn with rock dust, and your car will be, too, if you drive through there. No matter, this morning you turn south.

Arch Street Pike -- Highway 367 -- is a good road, nicely maintained and lightly traveled. It winds through southern Pulaski County for about 15 miles as measured from downtown, and then empties onto Highway 167 at East End. There the ride gets more complicated because the traffic is heavier, but this is 1964, not 2006, and we have not yet redefined "heavy traffic". Besides, it's Sunday morning, and you are about the only one not in church.

The air is cool and crisp so to take it all in the windows are down and the wind flows freely inside the car. Not to worry, you maintain an easy pace so the Brylcreem will keep the hair in place.

You pass Weasel's house, Base Line Road, Dixon Road, Willow Springs Road, Ironton Cutoff, Pratt Road (which, in eight more years, would lead to the Levi Strauss Distribution Center), and Iron Springs. Then you cross the line into Saline County and enter the community of East End. Two minutes later you come upon a site that you were about halfway anticipating because you've seen it before and you never get tired of it. There, on the west side of the highway, is a 40-acre lake, Lake Mary, and on the far side, spread out for several hundred feet along the shore, is a magnificent stone structure known as Marylake Carmelite Monastery. You pull to the side of the road and just sit and admire for a while.

It is 1964, and you wonder about the history of this place.

It is now 2006, and you know the history of this place.

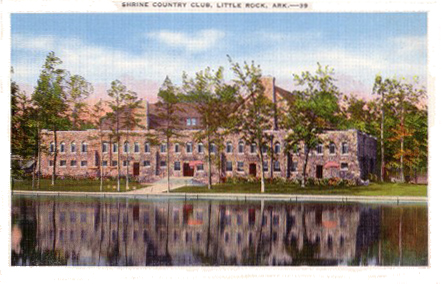

A postcard view of the lake side in 1925 |

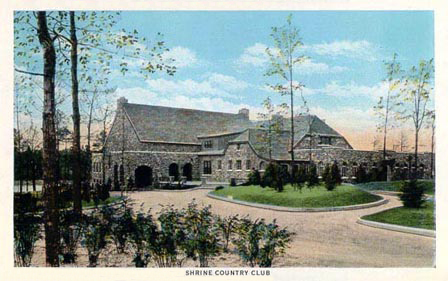

A postcard view of the side away from the lake |

What convinced the Little Rock Shriners that a country club 15 miles out a dirt road in the mid-1920s would be successful is not known. But apparently they thought it would work, so they obtained 365 acres of land, built a golf course and swimming beach, and constructed a clubhouse costing $100,000 ($1,150,000 at 2006 prices), and the property began life as the Shrine Country Club.

I haven't found the exact year they built it, and I don't know the exact year they sold it, but sell it they did and by the mid-1930s they were out of there.

Enter John Richard Brinkley.

Arkansas wasn't always the national repository of hillbilly jokes. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries the state was at the edge of the western frontier, and Little Rock, on a par with St. Louis, was one of the major cities and way points on the route west. Prior to statehood in 1836, Arkansas was a part of what was known as the Indian Territories, and a good portion of the state was awarded in the form of military bounty land warrants to those who had served honorably in the war of 1812. This distribution of land relocated families from Maine to South Carolina into the state of Arkansas. Additionally, the Arkansas River was open to shipping from New Orleans to Argenta (now North Little Rock). The hotels Marion, Lafayette, McGeHee, and Albert Pike were the equal of any in St. Louis or Atlanta, and the Missouri Pacific Railway Depot (born the Iron Mountain Union Depot), was one of the largest and most modern west of the Mississippi. Just look at the big granite and marble federal, state and local government buildings in Little Rock and on its periphery. These all represented a significant investment in the city's infrastructure.

But as the west opened up the migration left Arkansas and headed for the Pacific coast, and progress went with it. The hillbilly legend had begun innnocently in 1858 with a painting by Edward Payson Washburn called "The Arkansas Traveler", which depicts a rider on a horse who encounters a rural Arkansas family. (The painting hangs in the Old State House in Little Rock. You can see it HERE.) The painting circulated across the land and gained even more fame when Courier and Ives licensed it, and there was nothing to scotch the image that there was more to Arkansas than just that one scene, so the reputation grew and persisted. It spread further during the great depression of the 1930s when many Arkansans, mostly uneducated, unskilled farmers, left the state to try to make a living elsewhere, and it got a significant boost in the late 1940s when Hollywood began making movies like the ten-film Ma and Pa Kettle series, set in the Ozark Mountains. Although Arkansas was never specifically mentioned in the films, and the greater portion of the Ozark range is in Missouri, Arkansas' reputation was established and the state took the brunt of the imagery. It didn't help that when Percy Killbride retired as Pa he was replaced by Arthur Hunnicut, from Gravelly, Arkansas, for the last two films.

Along the way, one person who contributed a lion's share to the legacy was John Richard Brinkley. (You can Google the name to get more than the brief bio that follows.)

John Richard Brinkley, who sometimes used the middle name "Romulus", was one of the greatest medical quacks of the 20th century, and he was at his peak in Arkansas. He was born in 1885 in North Carolina, the son of a real doctor. In those days one could assume the role of a doctor just by doctoring, so JRB started doctoring. He eventually moved west into Arkansas, where he acquired a medical degree for $500 from a diploma mill, The Eclectic Medical University of Kansas City. Since the degree was accepted in Kansas, he went there and set up shop.

He specialized in curing men of waning libidos by implanting Toggenberg goat's gonads into the men's testicles, thereby imparting to them the sexual prowess of the Toggenberg, so he said. Many men swore by the procedure, so Brinkley decided to expand. He built a radio station, KFKB, and started advertising. The response was immediate, and so was the income. He needed more broadcasting power to reach further across the land. Refused by the Federal Radio Commission, who labeled his goat-gland operation fraudulent and revoked his license, he moved to Del Rio, Texas, where he built radio station XER across the border in Mexico. (XER, folks, later became XERF, from which, in the fifties and sixties, we would receive our late-night rock and roll and Wolfman Jack. See the Entertainment page HERE.)

Eventually, his ruse was exposed and he was forced to leave Texas. Incredibly, the state of Arkansas accepted his purchased degree and issued him a license to practice, so he set up shop in Little Rock at 20th and Schiller. To keep the authorities at bay, he had ceased his goat-gland operations and instead was offering prostate and rectal disease cures, all of which were on a par with his previous work. Paranoia being what it is, he was immediately successful once again, looked to expand, found the Shriner's Country Club out Arch Street Pike available, and moved in. He advertised it as "The World's Most Beautiful Hospital". But his reputation as a fraud was catching up to him. In the late 1930s, many men who were not helped by his procedures filed malpractice suits against him, the U.S. Government went after him for back taxes, and Mexico shut down his radio station. He filed bankruptcy, which ended his business, then had a series of heart attacks from which he died in May of 1942.

The Brinkley Hospital property at 20th and Schiller became the Village Inn Hotel.

The Brinkley Hospital property out Arch Street Pike was once again available. It was purchased by the Carmelite Brothers, and thus it is today.

Now you know.

If you want to see for yourself what a charlatan John Brinkley was, I have scanned the pamplet he handed out to his prospective patients in Little Rock. You'll find it HERE.

But first, enjoy the view below.

Marylake Carmelite Monastery, July 3, 2006